A Layperson's Summary of What I’ve Understood About Generative AI

Back to TopTo reach a broader audience, this article has been translated from Japanese.

You can find the original version here.

This article is Day 5 of the Summer Relay Series 2025.

The recent advances in generative AI technology have been remarkable, and even someone like me—whose recognition of AI was limited to "AI? Oh, you mean the golden robot from Star Wars"[1]—has become able to use AI reasonably well to carry out tasks.

I think it’s wonderful that you can use it even without fully understanding it, but in this industry—namely the side that provides generative AI technology and systems that leverage it—it’s better to have at least a general framework in mind when working.

There is a wealth of information about generative AI out there, but I couldn’t find anything that explains the concepts in an easy-to-understand way for amateurs[2], so I struggled in my initial learning. Therefore, based on what I’ve been able to understand so far, I’d like to compile this to help you get a rough sense of the world of generative AI.

Of course, this is a summary of what I, as an amateur, have learned from publicly available information, so it may include inaccuracies or misunderstandings. Naturally, the author is fully responsible for the content of this article.

Introduction: What Exactly Is Generative AI?

#The term AI is widely used, but I believe few (if any) can answer rigorously what is AI and what is not, or why there is a difference between the two.

The concept of AI itself is quite old, going back nearly 100 years to when machines first became capable of computation. Since the age of pioneers like Alan Turing, who created the code-breaking machine featured in the film “The Imitation Game,” and John von Neumann, who built the foundations of early computer theory, there have been attempts to have machines perform “human intellectual activities.” It was at a research conference known as the Dartmouth Conference in 1965 that John McCarthy coined the term “Artificial Intelligence,” which is thought to be the origin of the word AI.

In my interpretation, there seems to be no dispute that AI refers to machines that substitute for “intelligence ≒ human intellectual activity.” However, it is difficult to define exactly what “intelligence” is, and even Professor McCarthy himself admitted that it is hard to define intelligence rigorously without tying it to human intelligence. For example, calling throwing and catching a ball “intelligence” might feel odd in some contexts; it seems similarly difficult to pinpoint exactly what constitutes “artificial intelligence.” The goal of this article is not to define AI precisely, so if you understand it as machines (computers) that substitute for general “human intellectual activities,” I think you’ll find it easier to grasp the concept.

Saying “all human intellectual activities” covers such a vast area that the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence classifies AI challenges in its AI Map β2.0 as shown in the diagram below:

In the example of playing catch, the intelligent activity comprises various aspects: recognizing that “the white sphere is growing bigger,” analyzing that “the ball is flying toward you,” predicting “where the ball will arrive,” and controlling “the position of the glove.”

Generative AI is AI with functions centered around the generation and dialogue areas[3], and it is especially expected that it can substitute for human “intellectual labor” in the sense that it can create “new things (text, images, data, etc.)”[4].

Technologies Underpinning Generative AI

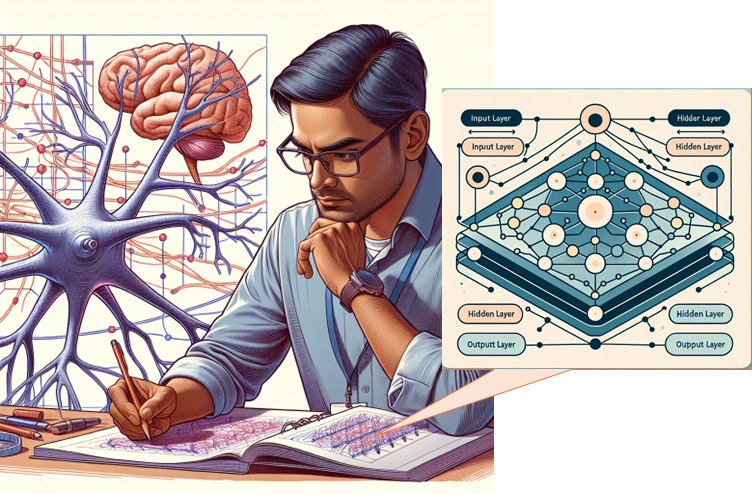

#When the concept of AI first emerged, there was a proposal for neural networks to recreate the function of human brain cells in a machine. It was known that human neurons operate by receiving multiple electrical inputs and then transmitting signals to the next neuron. The idea was to model a neuron that “outputs based on multiple inputs” and combine these models into a network to replicate brain function.

The constructed neural network produces an output for a given input, and by adjusting the network according to the output, you can tune parameters so that it produces the “correct ≒ expected by humans” results. Just as humans acquire knowledge through trial and error, this tuning stage is called the AI’s “learning.”

Since neural networks attempt to mimic the workings of the brain, there are various kinds[5] depending on how you model brain function. The specifics change according to the chosen model, but in any case, because they are networked models, they tend to require significant computational resources, which has led to cycles of boom and bust in their progress due to hardware limitations.

In 2017, researchers at Google introduced a model called the Transformer[6], which, unlike previous models, adopted a mechanism called “attention” to evaluate relationships in sequence data. This aimed to improve the performance of “sequence transformation,” such as machine translation, by allowing the evaluation of relationships even in vast inputs, thereby enabling natural (and plausible) outputs. This ability to assess relationships in large volumes of data, combined with advances in computing power, led to its application in generative domains. One of the catalysts for generative AI, OpenAI’s GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), is also a derivative of the Transformer model.

Being able to produce plausible outputs for inputs means that if you pre-train it on various information, the AI can generate “new” plausible outputs. You might compare it to someone who has studied a massive amount of Beethoven’s compositions and can then create a “new piece as if Beethoven had composed it”[7]. Based on my experience with current technology, I believe generative AI’s outputs have become quite close to those produced by humans.

The Impact and Limitations of Generative AI

#As generative AI has become capable of tasks close to human intellectual work, computers may soon share tasks that were previously difficult for anything but humans—such as “researching and compiling reports” or “analyzing requirements and performing suitable designs.” Because it can handle tasks that take humans a long time at high speed[8], there is potential for generative AI to dramatically improve productivity in these areas.

However, the content that AI outputs is not 100% accurate. This becomes clear when the instructions to the AI are poor[9], and issues such as hallucination—outputting inaccurate information—and misalignment—the emergence of “bad” AI—have been reported. Since this approach is based on the human brain, it’s natural that, like humans, AI can’t produce good results with vague instructions, may “tell lies as if it has seen them,” or may exhibit behavior that falls outside ethical norms.

Because generative AI can share intellectual labor, it might replace parts of human tasks. For instance, the ILO report states that a quarter of jobs will be affected. However, as the report itself notes, it seems difficult for human intellectual tasks to be completely replaced.

Whether the technical challenges mentioned above can be overcome is hard to say for someone who isn’t an expert, but even if those challenges disappear, there remains the problem that AI cannot make decisions. This is not a technical issue of AI capability, but a socio-structural issue: there is no consensus on who bears responsibility for “what AI decides.”

If an individual human performs an action, that person is responsible for it; if an organization does, the organization (or its responsible person) is. I believe this is the foundation of current society[10]. In other words, unless “who is responsible” is made clear when an AI-generated result causes a problem, AI cannot independently replace human work. Perhaps in the distant future we’ll live in a world where there is agreement that “it’s because AI did it,” but at present, it feels like there would be strong resistance to accepting AI responsibility when something goes wrong.

How We Should Engage with AI

#Though my experience is only from casually trying it out, at present I feel it’s better to think of generative AI not as a “machine that follows instructions to produce plausible outputs,” but more like a “(hardworking) new team member.” If you give it “clear instructions,” it will deliver results, but it can “make mistakes,” so you need to check its work, and the responsibility for any mistakes lies with the person who gave the instructions. Conversely, it also means that mundane tasks you might have assigned to a junior team member could be replaced by generative AI. The decline in entry-level job postings in knowledge-work markets in the U.S., for example, might be one indication of the rise (or anticipation) of generative AI[11].

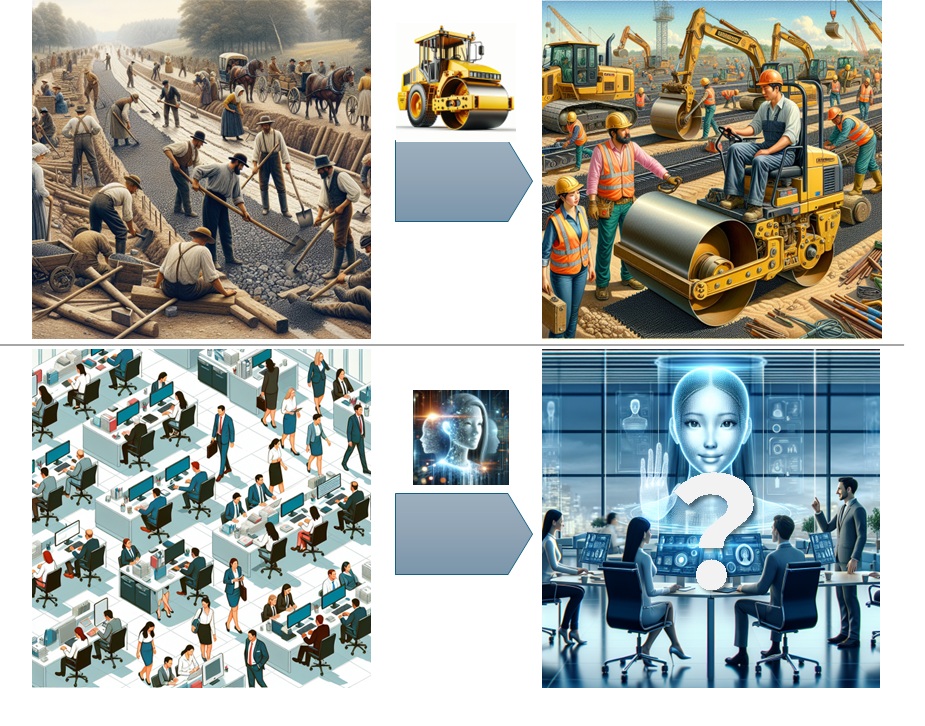

During the Industrial Revolution, labor-intensive tasks were transformed into capital-intensive ones through mechanical power like steam engines and internal combustion engines. For instance, with road construction, the great productivity gains from machinery meant that what once required large amounts of manual labor could be done with fewer workers by investing capital in construction machinery. I believe a similar structural shift is likely to occur in intellectual labor going forward.

Looking at it simplistically, it seems most efficient to reduce inexperienced workers and have a small number of “veterans” handle the work. However, over the long term, “veterans” retire with time, making it clear that business continuity would be difficult. It will become necessary to develop the skills for roles that humans must take on, considering how to divide labor with AI.

In road construction using heavy machinery, humans decide “where to cut and where to fill,” machines perform the actual tasks of “digging earth and moving stones,” and humans handle “problem-solving and adjustments” when issues arise. Similarly, although much remains unclear about how it will look in intellectual labor, certain areas will remain that humans must handle. Considering generative AI’s inability to “make decisions” or “take responsibility,” I feel that in future intellectual work, being able to “make decisions and take responsibility” will be a requirement for humans.

I’m no expert in education, but I think “thinking deeply and making decisions within your sphere of responsibility”[12]—or providing opportunities to do so—will become important for career development.

Summary

#I’ve compiled my amateur understanding of generative AI, from background to current capabilities and future outlook. I hope it can be helpful to anyone who is interested in generative AI but isn’t sure where to start.

This article doesn’t delve deeply into individual technical details, but on this developer site, through this relay series and various posts by experts, there’s plenty of in-depth information, so if you’re interested, please feel free to check them out.

You might not get the reference, but I think everyone, as a child, has had the experience of seeing robots talking to humans on TV or in movies and thinking, without fully understanding, “Oh, so that’s that AI thing!” That said, now that the technology has become widespread, we ironically seem to use the term “AI” less often—just as we don’t call Siri or Alexa “AI.” ↩︎

For example, if you hear “Generative AI is characterized by learning from existing data through deep learning techniques and generating new content that’s closer to human output,” without understanding the surrounding concepts, you’re left with questions like “Wait, what does it mean for a computer to learn?” or “How is deep learning related to generating new things?”—just a string of question marks, right? (That was the case for me.) ↩︎

It also seems to have capabilities around tasks like “analysis”/“estimation” of input information and “design” based on instructions when generating something. However, for grasping the concept, understanding it primarily as having a “generation” function should be sufficient. ↩︎

The expectation that it “might be able to substitute for intellectual labor” is inherent in the concept of AI itself. From my gut feeling, the level of expectation for generative AI differs from previous AI in that people engaged in intellectual work hold a real expectation (or sense of crisis) that they themselves could be replaced, rather than the more distant “someday this might be possible” dream of earlier AI. ↩︎

Famous examples include Deep Neural Networks (DNN) that enable deeper learning (deep learning) by stacking multiple layers of networks; Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) that excel in tasks such as image processing; and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) that can handle sequential data and thereby allow for contextual interpretation. ↩︎

The paper has a title that sounds like a movie or a song, “Attention Is All You Need,” but it has greatly contributed to the subsequent evolution of AI and is said to have a very high citation count. ↩︎

Just as there’s a difference in the quality of a Beethoven-like piece created by a child versus one created by a professional musician, the degree to which something is appropriate depends on the creator’s level of understanding. Since it’s modeling human intelligence, this is only to be expected, but it’s interesting that for generative AI as well, how you train (grow) it is crucial. ↩︎

You may have noticed that the illustrative diagrams in this article were created using generative AI. Although, with my lack of experience, they didn’t turn out “perfectly as I imagined,” if I had created them by hand, it would have taken several hours. Because I could produce them in a few minutes, I think the effects speak for themselves. ↩︎

Those who have used generative AI may know this well: for fairly clear instructions like “Please summarize this document in about 100 characters,” it gives quite good results. However, for cases where the input is huge or the request is vague—for example, “Explain Japan’s Sengoku period in a nice way”—the output tends to be unstable. ↩︎

For example, guardians share responsibility for their children’s actions, and we take out insurance for emergencies—society seems to break down responsibility to the level an individual can bear. This is just my sense as someone not specialized in social science, but I feel that, first and foremost, the involvement of the party directly concerned in taking responsibility is what makes society function; in other words, it’s the reason those around can absorb the problems that arise. ↩︎

Because economic conditions and other factors are involved, you can’t simply say “AI stole jobs,” but apparently a certain number of business leaders view that [simple or routine tasks can be replaced by generative AI]. ↩︎

For example, as an employee you’re often not in a position to make final decisions. However, within the scope of your assigned tasks, if you consider and decide “how to proceed” and then go to your manager for approval, I think you can gain decision-making experience without overstretching yourself. ↩︎