CCPM in Practice: Meet Deadlines Even with Half Buffers! How the Critical Chain Transforms the Workplace

Back to TopTo reach a broader audience, this article has been translated from Japanese.

You can find the original version here.

Introduction

#In the previous article “CCPM Theoretical Edition”, we explained TOC (Theory of Constraints), which forms the foundation of CCPM (Critical Chain Project Management). CCPM is a project management method that aims to shorten project deadlines and improve throughput by aggregating task buffers for overall management and maximizing the utilization of constraint resources. By visualizing the “hidden buffers” within individual tasks and optimally using them across the entire project, it enables the creation of more realistic and reliable schedules. This time, we’ll introduce how to apply CCPM to project schedule creation, and how the goals of “Meeting Deadlines Even with Half Buffers!” and the effects of “Transforming the Workplace with the Critical Chain” are realized.

CCPM is not just a technique for creating a schedule. It is an approach that combines both a way of thinking and a system to achieve the “shortest route” and “certain execution” necessary to fulfill project objectives. CCPM offers insights for structurally solving common project management challenges such as “missing deadlines” and “spending too much time on progress reports without moving forward.”

Why Schedules Are Not Adhered To

#Typical behavioral patterns can cause project delays.

-

The Multitasking Trap

Even when you’re executing an existing project, a new, urgent (expedited) project may be launched. When these overlap, work queues up, and productivity declines. -

Ad Hoc Resource Allocation

Managers or leaders sometimes neglect proper planning and fail to manage resources appropriately. -

Habit of Using Up Task Buffers

Even if a task finishes earlier than planned, it’s rarely reported, and as a result, all the allocated buffer tends to be consumed. -

Falling into Management for Management’s Sake

In an effort not to fall behind, too much focus is placed on management, leading to increased reporting and meetings, and ultimately to an excessive state of control.

CCPM was designed to address these four problematic behaviors structurally.

Step 1: Eliminate Multitasking

#Why You Should Focus on One Task

#When alternating between two tasks versus completing them one by one:

- Focusing on each task one at a time and completing them sequentially leads to faster completion.

- Focusing on each task one at a time and completing them sequentially also improves quality.

Even if we understand this, in reality, multi-project or multi-task scenarios are often unavoidable. Tasks that only a particular person can do tend to concentrate on that person.

If you want to delve deeper into the adverse effects of multitasking on work and strategies to counter them, please also see the previous article “No More Overtime! Escaping the Multitasking Trap and Delivering Results at Lightning Speed”.

Prioritizing and Focusing on Projects

#Define evaluation criteria from a management perspective, prioritize projects, and execute selection and concentration. The table below is one example where you set evaluation axes for projects, assess them, and determine priorities.

In this example, the evaluation axes are “Revenue,” “Profit,” “Strategic Importance,” and “Employee Motivation.” The ratings from top to bottom are ◎→〇→△→×, and in this case, the “Donut” project is given the highest priority.

Resource Allocation According to Priorities

#Allocate resources generously to the top-priority project. Even for projects judged to have lower priority and not started immediately, the responsible manager prepares thoroughly for their eventual start (e.g., reconfirming project objectives, updating schedules, preparing prerequisites for remaining tasks).

Step 2: Share the Project Goals

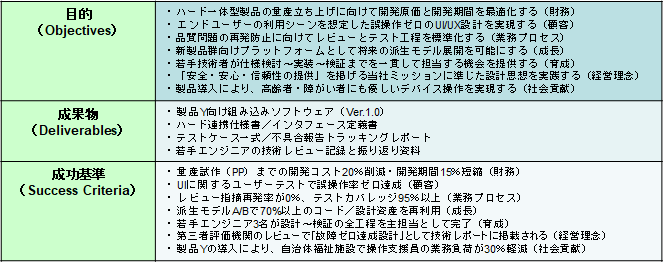

#Avoid vague goal setting and ensure a shared understanding among stakeholders by clarifying the ODSC.

-

Objectives (Objectives)

From diverse perspectives—finance, customer, business process, growth and development, corporate philosophy, and social contribution—enumerate the project’s objectives for each stakeholder. -

Deliverables (Deliverables)

Describe specifically what deliverables will be produced to achieve the objectives. -

Success Criteria (Success Criteria)

Clearly define project success criteria in externally observable terms.

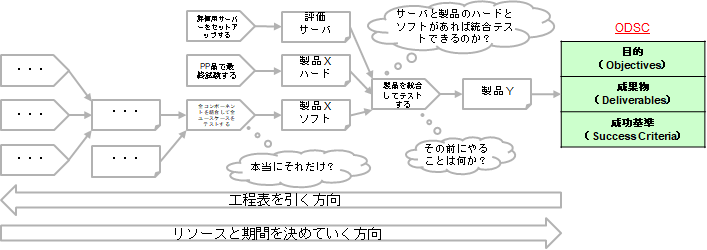

Step 3: Backward Planning from the Objectives – The “Success Scenario”

#Designing by Backward Planning from the “Success State”

#Rather than building a schedule by stacking tasks like in a WBS, construct it by tracing back from the ODSC (the vision of success) and asking “What is needed?” Specifically, starting from ODSC, identify the conditions for achieving the objectives in the sequence “Deliverable → Task → Deliverable → Task…”. To avoid omissions, repeat the following three questions while moving backward from the ODSC toward the project start until you reach the first task:

- What needs to be done before that?

- Is that really all?

- If you do XX, can you achieve YY?

Instead of a simple process name like “Final Test,” we recommend using the format “(Subject) will (verb) the (object)”—even if it becomes a bit lengthy—(e.g., “Perform the final test on PP items”). This clarifies the task’s purpose and completion criteria, making the definition easier for others to understand and making progress tracking more straightforward.

Allocating Resources and Duration

#Once all necessary tasks and deliverables are identified, starting from the first task toward the ODSC, assign who (the subject) will execute each task (allocate resources). Next, estimate how long each task will take when performed by the assigned resource, and record that duration. Finally, verbally read out, “Subject will (verb) the (object) in X days.” (e.g., “Takahashi will perform the final test on PP items in 10 days.”) This verbalization helps the assignee concretely imagine the work and is expected to improve estimation accuracy.

Step 4: Aggregate Individual Safety Buffers and Use Them as the “Project Buffer”

#We will now explain using the Gantt chart with the success scenario’s resources and estimated durations allocated.

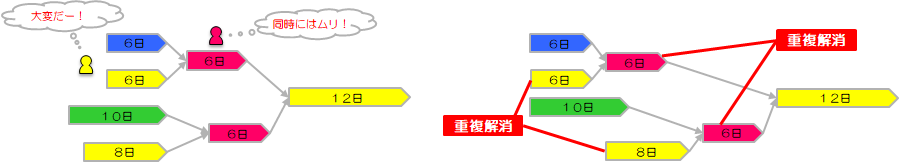

Eliminating Multitasking

#Remove resource overlaps and resolve multitasking. The task colors in the chart represent assignees; for example, three yellow tasks mean they are all handled by the same person. In the left Gantt chart, tasks for the same assignees (yellow and red) are scheduled in parallel (multitasking). To resolve this, adjust the schedule so that tasks for the same assignee do not overlap, as shown in the right Gantt chart.

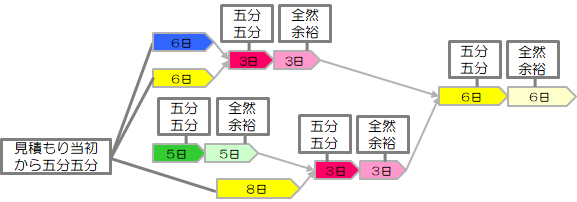

Identifying Safety Buffers

#Task owners often unconsciously pad their work durations with safety buffers due to a strong sense of responsibility or mission to meet deadlines. This tendency is especially seen in diligent individuals—they include more safety buffer to ensure they meet deadlines. Confirm with each task owner the breakdown of their task duration and separate “safety buffer” from the “time required for a 50% probability of completion” (actual work duration). If the confirmed duration already represents a 50/50 completion probability, adopt that duration as is.

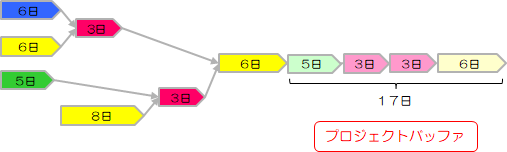

Aggregating Safety Buffers and Creating the Project Buffer

#Aggregate the safety buffers extracted from each task and place them after the final task as the overall project buffer. This is called the Project Buffer.

Determining the Deadline

#By estimating each task’s duration as the time required for a 50% probability of completion, the excessive safety buffers originally included in individual tasks have been aggregated into the project buffer. The probability that all tasks will require their maximum safety buffer is low. Therefore, even if you set the aggregated buffer to about half, the project buffer can still absorb delays adequately, resulting in a realistic schedule. This aggregation and optimization is precisely what underpins the efficiency and high reliability of project management touted in the title—“Meeting Deadlines Even with Half Buffers!”

However, halving the project buffer should be considered only a guideline. The final deadline should be decided by the project manager in consultation with management, considering the project’s characteristics and acceptable risk levels from a business perspective.

Step 5: Identify the Critical Chain

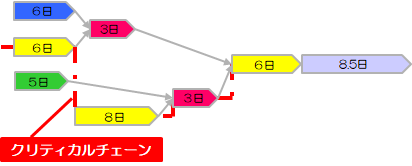

#Identifying the Critical Chain

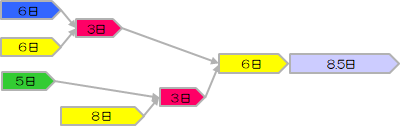

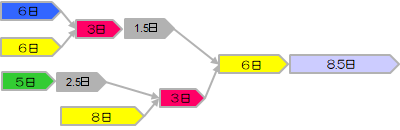

#Find the longest series of tasks (path) that determines the total project duration.

In the example above, the sequence “6 days → 8 days → 3 days → 6 days” forms the longest path determining the project’s total duration. In CCPM, this longest path—calculated by considering resource constraints and determining the overall project duration—is called the “Critical Chain.”

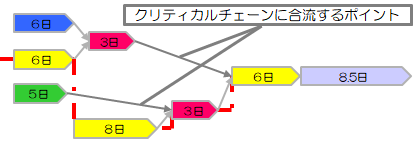

Prepare Feeding Buffers

#Tasks on the Critical Chain are extremely important as they influence the overall project duration, but you also need to consider points where other tasks merge into the Critical Chain.

As a risk measure, insert safety buffers just before merge points so that delays in tasks coming from non-critical chain paths do not affect the Critical Chain.

These safety buffers function to protect the Critical Chain from delays and are called “Feeding Buffers.” In the sample Gantt chart above, the Feeding Buffers are set to half the duration of the non-critical tasks. With the Project Buffer, the Feeding Buffers, and the resource-constraint–aware Critical Chain, you combine these to create a “realistic schedule” that addresses uncertainty while driving toward project goals. Focusing on the Critical Chain clarifies daily work priorities and strengthens team collaboration, thereby positively transforming the project work environment itself.

Bonus: Differences between the Critical Path and the Critical Chain

#Generally, the Critical Path Method (CPM)—also included in the PMBOK®ガイド—is more widely known and used. The Critical Path in CPM is the sequence of tasks with dependencies and durations that takes the longest time to complete and thus determines the project end date. Meanwhile, in CCPM, the Critical Chain also takes into account resource availability (for example, when specific personnel or equipment cannot handle multiple tasks at the same time), in addition to dependencies. This allows for creating an optimal schedule that reflects realistic resource constraints and identifying the path that most impacts the deadline as the Critical Chain.

Conclusion

#In this article, we’ve provided concrete steps for putting CCPM into practice to create a “realistic schedule drawn by the Critical Chain.” By aggregating and optimizing individual task buffers and identifying the Critical Chain that reflects resource constraints, you can see a path to overcoming the challenges of traditional methods. CCPM is not just a technique; it also has the potential to transform the behaviors and mindsets of those involved in the project. We hope this article helps you solve challenges in project management and leads to more “realistic” and higher-probability-of-success project execution.

Next time, in “CCPM Tools Edition,” we plan to introduce how to automate the identification of the Critical Chain and the setting of Feeding Buffers using tools (Google Sheets + Apps Script). We’ll share implementation examples that streamline reflecting resource constraints and buffer calculations—which are difficult to do manually—so please look forward to it.