Considering Embedding Mutation Testing into Development

Back to TopTo reach a broader audience, this article has been translated from Japanese.

You can find the original version here.

In the previous article, I introduced the Java mutation testing tool PIT (PiTest)[1]. Mutation testing is a promising technology for evaluating the quality of tests, and using PIT allows for simple test evaluations without crafting elaborate configurations.

However, since it is an approach that mechanically incorporates mutations, there are points that should be considered if you intend to use it in daily development. Continuing with the "Common Sample Application" that we have been using in the previous article, let's consider what kind of ideals are desirable.

The code samples of this article are available in the GitLab repository, so please use them if you're interested.

Assumed Development Scenario

#To evaluate the sufficiency of tests before release, we performed mutation testing (analysis) on the "Common Sample Application" using PiTest and were able to reinforce tests that were insufficient. While it was good that we could detect test deficiencies before release, scrambling at the last moment due to insufficient tests isn't good for the heart. Ideally, we want to detect any test deficiencies during daily development so we can approach release with peace of mind.

As a matter of fact, it took tens of seconds to execute PiTest. If it takes this much time in the early stages of development, where the number of tests executed is still small, it's risky[2] to continue using it as it is. Therefore, I decided to review the settings of PiTest to see if it can be used in daily development without strain.

Breakdown of Test Execution Time

#As I mentioned in the previous article, mutation testing is an approach where the target code is mechanically modified and the tests are executed. That is, simply put[3], the total execution time is the multiplicative effect of "the places where modifications can be inserted," "the mutation contents to be added," and "the execution time of the (original) tests."

Looking at the execution logs, most of the processing time is occupied by "coverage and dependency analysis," which is the preparation for modifications, and "run mutation analysis," which is the execution and result analysis of tests for each mutation. In other words, by adjusting without waste each of the code to be modified, the mutation patterns, and the test code to be executed, and if we can set up the necessary and sufficient mutation analysis, there is a possibility to shorten the required time.

Narrowing Down the Code to be Modified

#PiTest modifies the behavior of the test target by applying "mutators" that make certain modifications to the compiled bytecode, and evaluates whether the modified behavior is detected as a test failure. In other words, it's assumed[4] that executing it again on source code (product code/test code) that hasn't changed will yield the same results.

In other words, mutation testing can be said to be a technology that can efficiently provide feedback if it is executed only on source code that has changed since the "previous mutation test results." For such use, PiTest provides features such as incremental analysis and specifying target classes for analysis.

Incremental Analysis

#As of this writing, although it's experimental, PiTest provides a feature called incremental analysis that performs mutation testing on code changes (increments).

Incremental analysis saves information about the target source code (product code/test code) when mutation tests are executed. By using this information as input in the next execution, it assumes that the results will not change for parts that have no "changes since the previous execution," and excludes them from the analysis targets.

The behavior of the test target is mainly controlled by the manipulated source code (compiled bytecode), but even if the source code is not changed, the behavior of the test target may change due to changes in its dependencies.

PiTest determines the presence or absence of changes based on the hypothesis that the impact of changes in dependencies is limited only to the super class and outer class, which are "the most strongly dependent" elements.

I think the fact that this logic is based on a "reasonable but not proven" hypothesis is also one of the reasons why incremental analysis is provided as an experimental feature.

When using incremental analysis, you specify the input source (historyInputLocation) and output destination (historyOutputLocation) for PiTest's execution information as shown below. If you want to perform mutation testing targeting the differences since the previous execution, you can set the same path for both so that the previous results output to the "output destination" become the "input source" for this time. In special circumstances such as "developing while switching between multiple branches," the results in the "output destination" may differ from the previous results you are seeking, so some ingenuity such as changing the settings each time may be necessary.

As a simpler setting, you can also set the "temporary directory" as the history input/output location by setting withHistory. However, in the case of the Gradle plugin, it seems that the build directory is set as the temporary directory, so be aware that the history will also be initialized when executing the clean task with this setting.

pitest {

・・・

// Set the input/output location for the mutation test history data

historyInputLocation = ".mutation/history"

historyOutputLocation = ".mutation/history"

// It's also possible to set the temporary directory as the history save location for a simpler setting. When this setting is used, configurations like InputLocation are ignored

// withHistory = true

}

For example, in a situation where you are holding the pre-improvement state of mutation coverage from the previous article as history, if you improve the test code and execute the pitest task, it detects from the history that there were changes in the test code (GreetServiceTest), and mutation testing is performed targeting only GreetService.

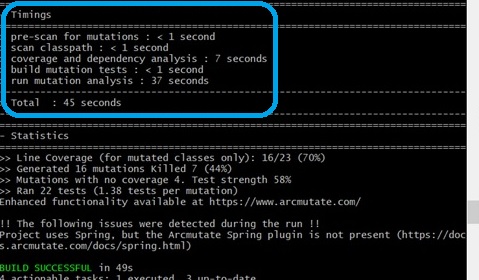

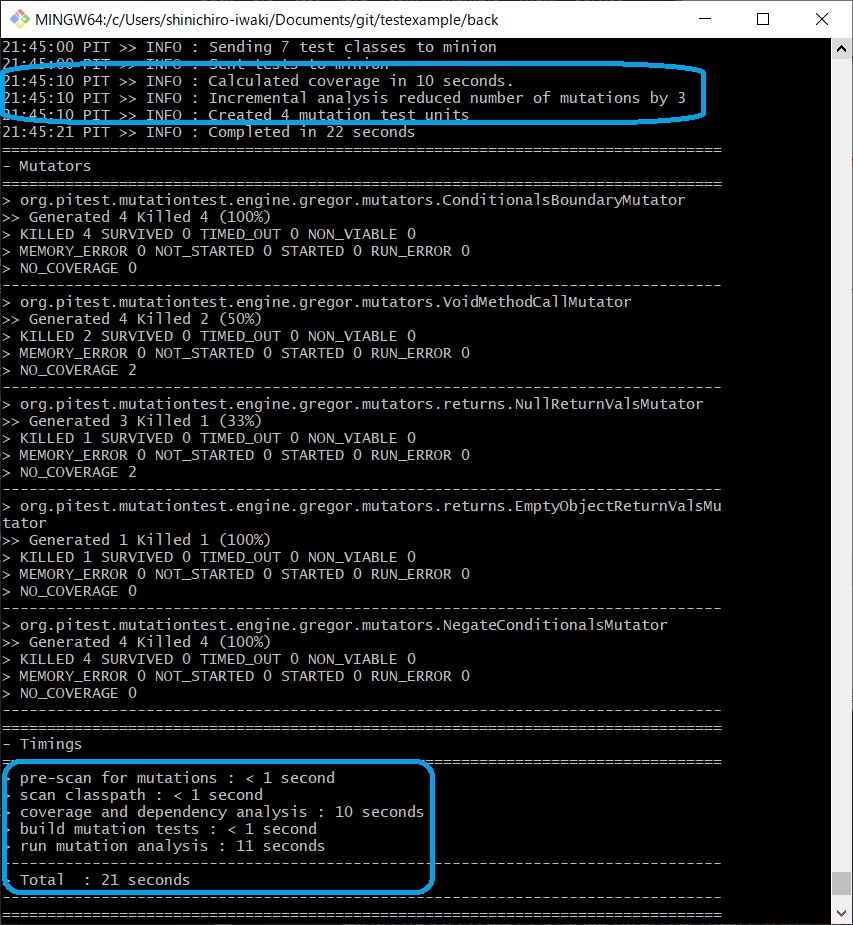

Looking at the execution log, mutations were reduced by incremental analysis ("Incremental analysis reduced number of mutations by 3"). Although the processing time for dependency analysis in the preparation stage increased, the test execution time was reduced to about half, and the total execution time was shortened.

Specifying Classes for Analysis

#If you use incremental analysis, you can easily perform mutation testing with a narrowed target. However, since it operates based on the differences from the "previous execution," in cases where you want to perform mutation testing on code that has differences between branches before merging, some operational ingenuity is required.

In cases like "before merging," you can also utilize difference information managed by source control tools like Git.

In PiTest, you can set the classes to be mutated and the test classes as shown below. If targetTests, which specifies the test classes, is not specified, targetClasses is used as the test class setting, so be careful when specifying the classes to be modified with specific class names.

pitest {

・・・

// Specify the target mutation classes and the test classes to be executed as arrays. Wildcards can be used.

targetClasses = [ "com.example.iwaki.service.GreetService","com.example.iwaki.BackApplication" ]

// If the test class to be executed is not specified, the same value as targetClasses is set, so it is recommended to explicitly specify the test classes

targetTests = [ "com.example.iwaki.service.*","com.example.iwaki.*" ]

}

By reflecting information about changes extracted from SCM management information in this setting, you can specify the target classes. Modifying build.gradle every time you build is cumbersome, so it would be convenient to make it changeable via runtime options or environment variables. For example, you can specify the (default) target via Gradle properties, and switch settings using runtime options (-P) or environment variables (GRADLE_PROJECT_XXX)[5].

- gradle.properties

// By defining default settings in Gradle's project properties, etc., they can be changed externally via runtime options

PITEST_TARGET_CLASSES="com.example.iwaki.*"

PITEST_TEST_CLASSES="com.example.iwaki.*"

- build.gradle

----

pitest {

・・・

// Convert the settings values in gradle.properties to arrays and set them

targetClasses = [ PITEST_TARGET_CLASSES ]

targetTests = [ PITEST_TEST_CLASSES ]

}

If you specify the changed classes as targets, you can shorten the test execution time similarly to incremental analysis. It's convenient to use them differently depending on the purpose, such as using incremental analysis when developing on the same branch, and utilizing SCM information when checking changes before merging.

In PiTest's Maven plugin, there is a goal called scmMutationCoverage that performs mutation testing targeting changed files by collaborating with Maven's SCM Plugin.

One reason why such functionality is not provided in the Gradle plugin may be the characteristic of the tool that detailed processing necessary for the build can be implemented by each person through tasks (such as custom plugins).

Note that there are some 3rd party plugins in Gradle that integrate with SCM, but as far as the author confirmed, development had stopped or they were for limited purposes.

When executing PiTest from Gradle using SCM information, it seems safer to consider manipulating SCM outside of Gradle (for example, in a CI job, retrieving information from the SCM tool before executing the Gradle task and passing it to Gradle).

Narrowing Down the Executed Test Code

#I have separately described the possibility of optimizing processing by executing mutation tests limited to code that has changed since the previous results. In addition, you can aim to shorten the required time by excluding test code that takes a long time to execute, such as integration tests or end-to-end test code, from the mutation test targets.

In the "Common Sample Application," the Contract Tests using Pact take a long time. This test verifies combinations of responses (contracts) to calls from the frontend, which is the consumer side, and is a test to evaluate the coupling possibility between services. Since it is a test to evaluate coupling with other services (before actually coupling), it was of little meaning[6] to evaluate sufficiency by introducing mutations.

Similarly to specifying the targets for mutation testing, you can specify classes or test classes to exclude as follows.

pitest {

・・・

// Specify classes and test classes to be excluded from mutation as arrays. Wildcards can be used.

excludedClasses = [ "com.example.iwaki.BackApplication","com.example.iwaki.ClockConfig" ]

excludedTestClasses = [ "com.example.iwaki.controller.GreetContractTest" ]

}

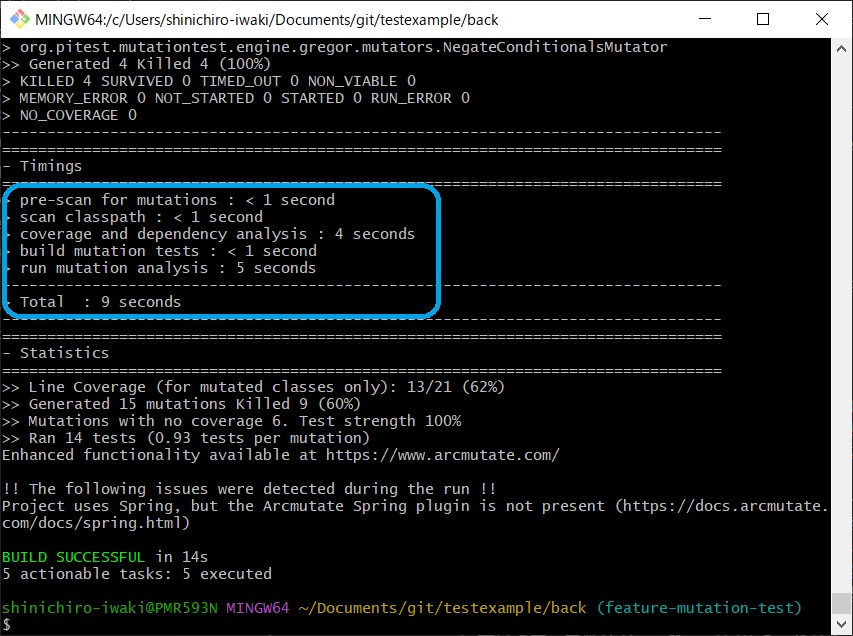

By excluding classes like Contract Tests that have long processing times and classes such as Config which have little meaning to be mutation test targets from the execution targets, we could confirm an improvement in execution time.

In this article, I introduced examples of setting targets/exclusions on a per-class basis, but it's also possible to set them on a per-method basis (excludedMethods/includedTestMethods) or per testing framework group (includedGroups/excludedGroup).

Narrowing Down Mutation Patterns

#At the time of writing, embedding mutations into the test target has 11 types enabled by default, as shown in the table below, according to the official documentation. Also, mutators, which are the logic that adds mutations, are provided in addition to those in the table below, and you can change the mutators to use by specifying individual mutator names or group names provided by the tool.

| Mutator | Overview | Examples of Test Omissions Detected (Note) |

|---|---|---|

| CONDITIONALS_BOUNDARY | Shift boundaries of comparison operators (> → >=, etc.) |

Missing boundary value tests |

| INCREMENTS | Flip increment/decrement (++ → --, etc.) |

Missing tests for multiple inputs in loop processing |

| INVERT_NEGS | Negation of numeric variables (i → -i, etc.) |

Insufficient value verification (including cases where whether it's positive or negative doesn't affect) |

| MATH | Change mathematical operators (a + b → a - b, etc.) |

Insufficient value verification (including cases where incorrect operators don't affect, such as 0 + 0) |

| NEGATE_CONDITIONALS | Flip comparison operators (== → !=, etc.) |

Missing tests for equivalence classes (e.g., tested x == a but not x != a) |

| VOID_METHOD_CALLS | Deletion of void method calls (methods with no return value) | Missing tests for the effects of the relevant methods (postconditions, etc.) |

| EMPTY_RETURNS | Change method return values to empty values corresponding to their types (e.g., return "" for string type) | Missing tests for empty values in subsequent processing |

| FALSE_RETURNS | Change return values of methods returning boolean to false | Missing tests for patterns based on the results of the relevant methods |

| TRUE_RETURNS | Change return values of methods returning boolean to true | Missing tests for patterns based on the results of the relevant methods |

| NULL_RETURNS | Change return values of methods (without NotNull constraints) to Null | Missing tests for Null patterns in subsequent operations |

| PRIMITIVE_RETURNS | Change return values of primitive numbers (int, float, etc.) to zero | Missing tests for patterns leading to division by zero in subsequent operations on return values |

Note: Estimated by the author based on the mutation content

Since mutations to the test target are due to the action of mutators, it's assumed that there is a certain correlation between the number of mutators used and the number of mutations added. For test omission patterns that are less likely to occur due to development techniques or frameworks used[7], you might be able to shorten execution time by narrowing down the mutators.

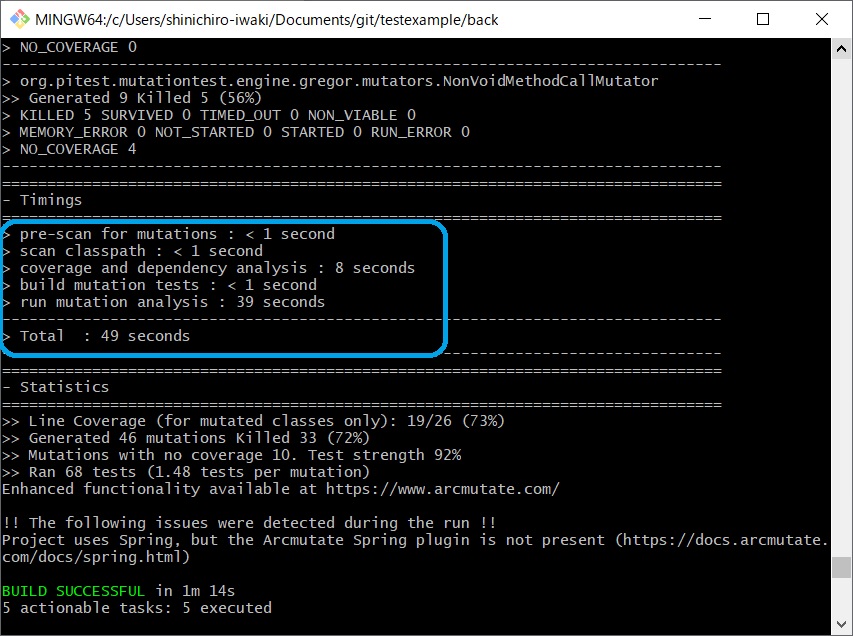

This time, since there is little basis for removing each of the mutators that are set by default, I'll just confirm that the required time increases when the number of mutators is increased.

pitest {

・・・

// Specify the mutator names to use, or the group names bundled by the tool

mutators = [ "ALL" ]

}

Conclusion

#I introduced settings to shorten the "execution time," which could be an obstacle to utilizing the mutation testing tool PiTest that I introduced previously. While it's unavoidable that it takes more time compared to normal tests, if you set the analysis targets appropriately, it might become practically usable.

Those who were checking the schedule may have noticed, but the title of this article is the one I had planned to post on the 3rd day of the Advent Calendar. I tried to include this content in the previous article, but it seemed the volume would become large, so I decided to split it... Let's just say that. ↩︎

This sample application includes tests that have relatively long execution times, such as Contract Tests using the Pact broker. That said, at the time of the previous article, there were 4 target classes and 2 test classes, and it still took tens of seconds. It's not hard to imagine that when the number of target classes reaches the hundreds, the execution time will increase to minutes or hours. If the test execution takes 1 hour, it might be acceptable to run it once before release, but using it in daily development would be a bit hesitant. ↩︎

In reality, since the processing runs in parallel, it doesn't increase in such a simple multiplicative manner. However, since the approach is "modifying the target code, executing the (original) tests on it, and evaluating whether the modifications were detected as test failures," I think the tendency is correct. ↩︎

Theoretically, there may be cases where the result changes even without changes in the source code, such as when the mutator generates different modifications each time it runs. However, based on the concept of the technology, such cases should be evaluated as issues with the tool. ↩︎

The official plugin documentation introduces the method of overriding settings using the gradle-override-plugin to override settings. However, since it seems that this plugin has limitations such as overriding array values, I took the form of converting the property (specified as a comma-separated string) within build.gradle into an array. ↩︎

In terms of the test purpose here, that is indeed the case, but for example, when taking an approach where the content at the unit test level of the Controller class is covered in integration tests, etc., simply excluding integration-level tests may result in many "uncovered" areas in the overall test. When narrowing down the target code for mutation testing, it would be good to be able to make a judgment considering the overall test approach. ↩︎

For example, when adopting test-driven development, where you "define the behavior of the test target in the test code and then modify the target to satisfy it," it's less likely for test patterns such as "missing equivalent classes for certain conditions" to occur in the implemented code. In this case, the value of using the NEGATE_CONDITIONALS mutator may relatively decrease. ↩︎