How to Implement UML in a Programming Language? C Language (Super Simple Version)

Back to TopTo reach a broader audience, this article has been translated from Japanese.

You can find the original version here.

Introduction

#When teaching seminars on UML notation and UML modeling, I often receive questions like, "How should I implement this in my language?" As an instructor, I've also experienced that explaining UML in the programming language that participants use helps them understand it more easily. It seems that many programmers are interested in UML modeling, but surprisingly, not many know how to translate UML models into source code. I believe this might be one of the reasons why UML modeling hasn't become more widespread.

The conversion from UML to source code is called "mapping," and it is referred to with the programming language name, like "UML/C++ mapping." This series is designed to introduce "UML/X mapping" to various programming languages, allowing you to understand UML from the perspective of familiar programming languages. However, there are various ways to consider mapping. The examples provided are just one way to do it.

Basic Knowledge Required to Understand This Article

#This article assumes you have a minimal understanding of UML notation. For example, you should understand how to read attributes/operations and association end names/multiplicity and visibility in class diagrams, the meaning of generalization/realization relationships, and the correspondence between messages in sequence diagrams and class operations.

Mapping Policy in This Article

#This article targets those who use UML but are more familiar with C language and may be confused by concepts like "class" and "instance." It introduces an approach where you draw class diagrams treating all instances as classes without distinguishing between classes and instances, and then convert that diagram based on mapping.

The mapping method does not address UML's protected, package, generalization relationships, or multiplicity. The basic mapping method is simply to prefix variable and function names with the "class name."

The advantage of this method is that "there is no need to understand the concept of classes and instances, lowering the entry barrier." For example, instead of a "Motor" class, the class diagram would depict two classes: "Right Motor" and "Left Motor."

On the other hand, the disadvantage is that "if the same class exists multiple times, you end up creating almost copy-paste modules." For instance, you would create files like "RightMotor.c" and "LeftMotor.c" and write the same "start function" code in each. Therefore, when fixing bugs or adding features, you need to address each file individually.

Based on the above policy, this article does not cover many UML notations and uses a limited set of notations to create class diagrams, which are then mapped to code.

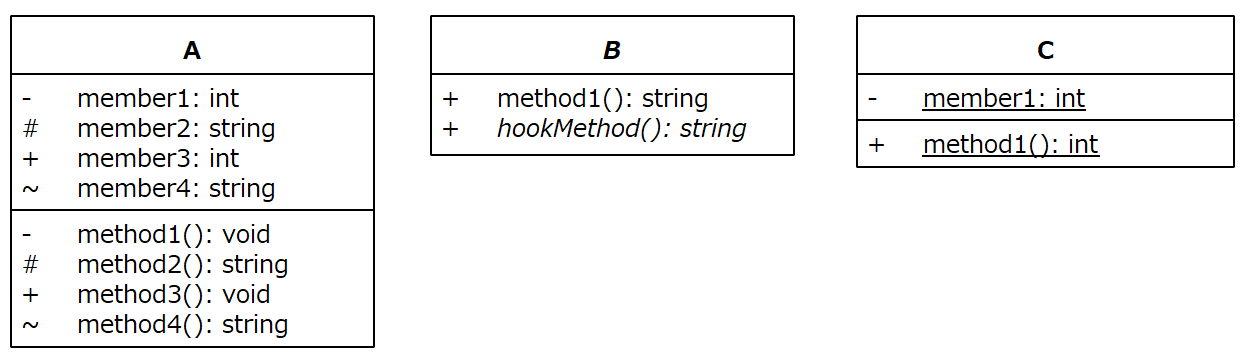

Mapping of Basic Class Elements (Class, Attribute, Operation)

#A.h

#ifndef A_H

#define A_H

// public attribute

extern int A_member3; // Add extern to indicate external linkage for variables

// public method

void A_method3(); // Generally, extern is not added to function declarations as it is implicitly added by default

#endif

A.c

#include "A.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

// private attribute

static int A_member1; // Add static for private attributes

// ※ This sample treats the file as a class unit,

// utilizing the scope of static variables within the file.

// protected attribute

// static char member2[100]; // Not supported for protected

// public attribute

int A_member3; // No need for static for public attributes

// package attribute

// char A_member4[100]; // Not supported for package

// private method

static void A_method1() { // Add static for private methods

// Implementation of private method method1

}

// protected method

// char* A_method2() { // Not supported for protected

// // Implementation of protected method method2

// return member2;

// }

// public method

void A_method3() { // No need for static for public methods

// Implementation of public method method3

printf("A_method3 was called\n");

}

// package method

// void A_method4(char* output) { // Not supported for package

// // Implementation of package/private method method4

// strcpy(output, A_member4);

// }

B.h

#ifndef B_H

#define B_H

// public method

char* B_method1();

// public abstract method

// char* B_hookMethod(); // Abstract methods are not supported

#endif

B.c

#include "B.h"

#include <string.h>

// public method

char* B_method1() {

// Implementation of method1

strcpy(result1, "Result of B_method1");

return result1;

}

// public abstract method

// char* B_hookMethod() {

// // Implementation of hookMethod

// strcpy(result2, "Result of B_hookMethod");

// return result2;

// }

C.h

#ifndef C_H

#define C_H

// public method

int C_method1();

#endif

C.c

#include "C.h"

// private attribute

static int C_member1;

// public method

int C_method1() {

// Implementation of method1

return C_member1;

}

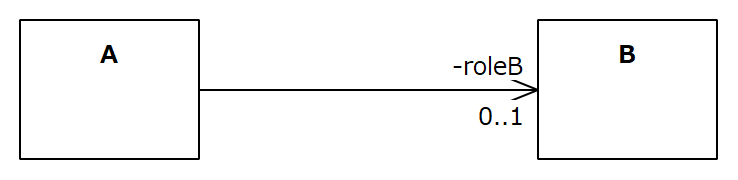

Mapping of Association (Unidirectional Multiplicity 0..1)

#Since the policy does not consider instantiation, it does not support multiplicity. When drawing class diagrams, do not specify multiplicity like 0..1 or n..m.

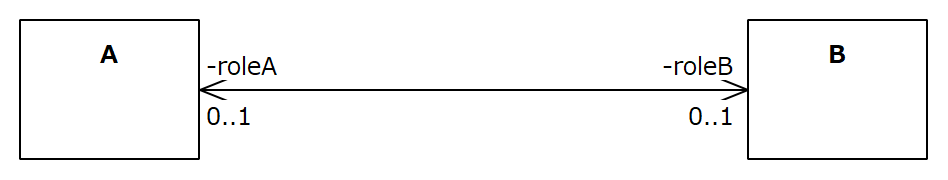

Mapping of Association (Bidirectional Multiplicity 0..1)

#Since the policy does not consider instantiation, it does not support multiplicity. When drawing class diagrams, do not specify multiplicity like 0..1 or n..m.

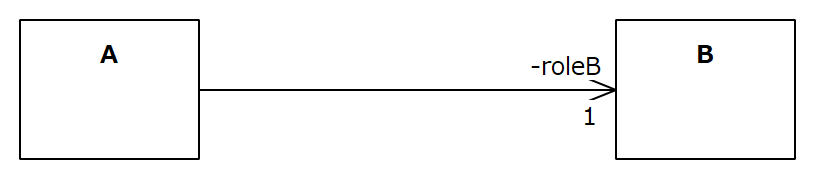

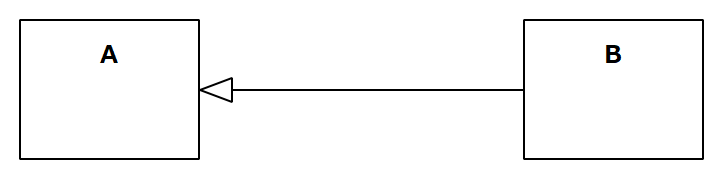

Mapping of Association (Unidirectional Multiplicity 1)

#In this mapping policy, this is almost the only way to link between classes. The mapping is the same even if it is bidirectional.

A.h

#ifndef A_H

#define A_H

// public method

void A_executeSomething(); // Sample code includes a function call to class B.

#endif

A.c

#include "A.h"

#include "B.h" // Include to use methods of class B

// public method

void A_executeSomething() {

// Implement processing

B_executeSomething(); // Call method of class B

}

B.h

#ifndef B_H

#define B_H

// public method

void B_executeSomething(); // Method of class B to be called

#endif

B.c

#include "B.h"

// public method

void B_executeSomething() {

// Implement processing

}

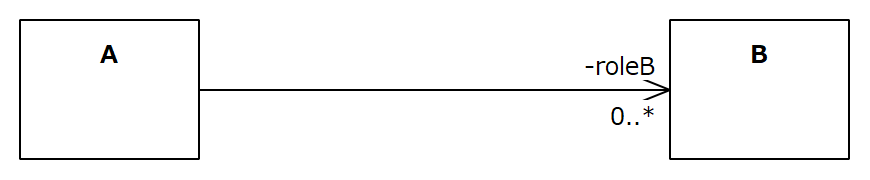

Mapping of Association (Unidirectional Multiplicity 0..*)

#Since the policy does not consider instantiation, it does not support multiplicity. When drawing class diagrams, do not specify multiplicity like 0..1 or n..m.

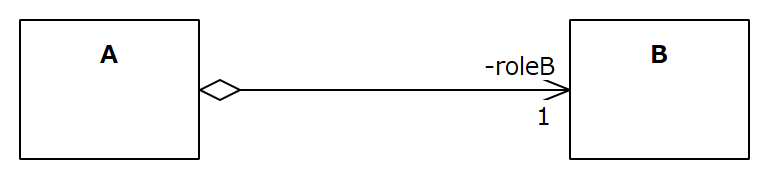

Mapping of Association (Aggregation)

#The mapping is the same as "Mapping of Association (Unidirectional Multiplicity 1)." However, in class diagrams, using aggregation to express the whole-part relationship is not meaningless.

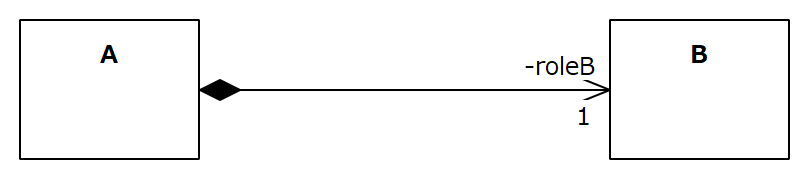

Mapping of Association (Composition)

#Composition indicates a relationship where the lifecycle constraint causes the instances of the part concept to disappear when the instance of the whole concept disappears. However, since the policy does not consider instantiation, instances do not disappear. Therefore, the mapping is the same as "Mapping of Association (Aggregation)" and "Mapping of Association (Unidirectional Multiplicity 1)."

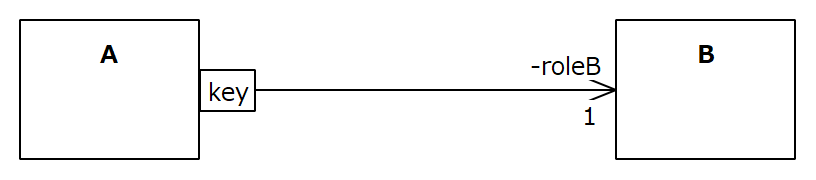

Mapping of Association (Qualifier)

#Since the policy does not consider instantiation, it does not support qualifiers for cases with multiplicity. When drawing class diagrams, do not specify qualifiers.

Mapping of Generalization (Inheritance Mapping)

#In languages with inheritance mechanisms, implement using inheritance, but in languages without such mechanisms, implement using embedding.

Generalization itself cannot be supported in C language.

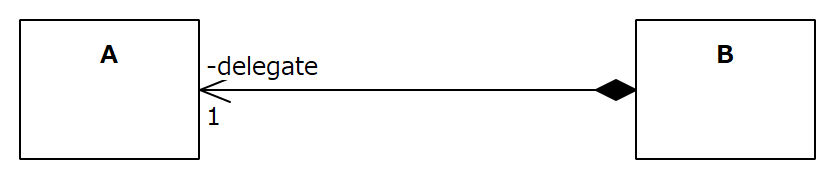

Mapping of Generalization (Delegation Mapping)

#Implementation through inheritance results in a stronger coupling between the base class and the derived class, so delegation is sometimes used to intentionally reduce coupling.

When a function on the class A side is called from outside, it cannot behave as class B. However, when a function on the class B side is called from outside, it is possible to implement it by calling a function of class A within class B. The code is just the reverse direction of "Mapping of Association (Unidirectional Multiplicity 1)."

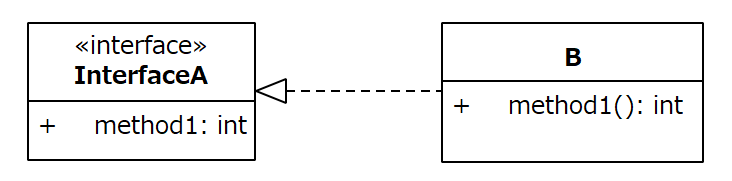

Mapping of Realization

#The interface of the realization corresponds to the .h file, and the realization class corresponds to the .c file. In this class diagram, there is only "Class B," but it is possible to create another .c file that implements the same "Interface InterfaceA." If you want to replace the realization class, do so with the linker. Dynamic replacement at runtime is not possible.

InterfaceA.h

#ifndef INTERFACEA_H

#define INTERFACEA_H

// Prototype declaration of methods corresponding to InterfaceA

int InterfaceA_method1();

#endif

B.c

#include "A.h"

// Implement interface methods in B

int InterfaceA_method1() {

// Implementation of InterfaceA_method1

return 0;

}

C.c

#include "A.h"

// Implement interface methods in C

int InterfaceA_method1() {

// Implementation of InterfaceA_method1

return 1;

}

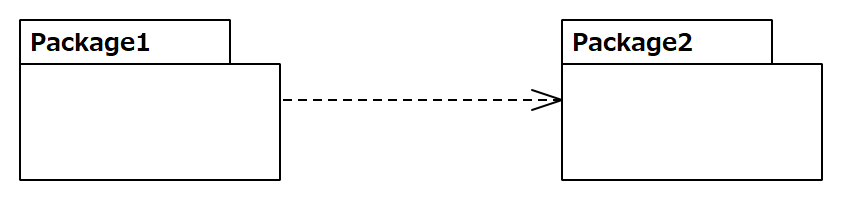

Mapping of Package Diagram Dependencies

#Packages cannot be implemented in code, but they can be realized by organizing files into folders.

Conclusion

#This article may be updated in the future. Please check for the latest information when using it.