Getting Started with Property-Based Testing in Kiro: Uncovering the Unexpected

Back to TopTo reach a broader audience, this article has been translated from Japanese.

You can find the original version here.

This is the article for the 17th day of the Mamezou Developer Site Advent Calendar 2025.

1. Introduction: Why Try PBT Now?

#Property-based testing (hereafter PBT) is a testing methodology that verifies the "properties" that should be satisfied, extracted from the specification, against arbitrary inputs, states, and sequences of operations. It is known that PBT has a complementary relationship with traditional example-based testing (EBT)[1].

To be honest, I suspect many people don't quite get it from that explanation alone. I myself had been interested for some time but felt that formalizing the behaviors to be satisfied was difficult and that the implementation cost seemed high, so I hadn't ventured into it.

However, on November 17, 2025, Kiro reached GA and introduced 'Correctness verification with property-based tests' as an IDE feature[2]. Thanks to this new feature, the barrier to introducing PBT seemed to be lowered, so I decided to actually get my hands dirty and try it out.

For Kiro's PBT feature, please refer to the official documentation "Correctness with Property-based tests".

2. Why PBT: The Decisive Difference from EBT

#In the book 『実践プロパティベーステスト』[3], PBT's characteristics are explained as follows:

It is not a method of writing a ton of examples for tests or generating random data to throw at the code, but rather a technique for finding new, unexpected bugs that lurk in the code.

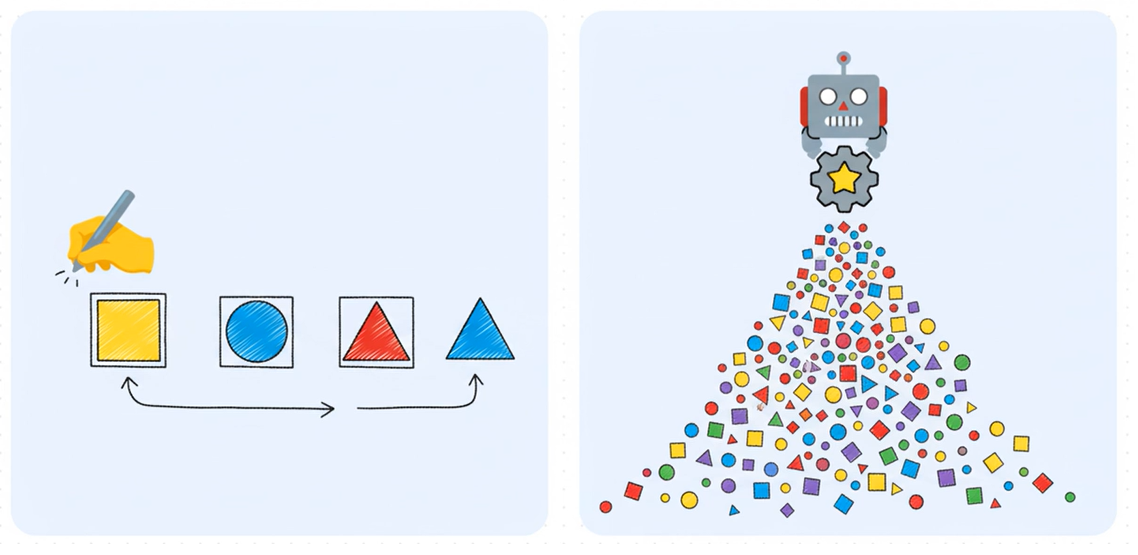

Let's think of a concrete example. In traditional example-based testing (EBT), you check specific examples like "1 plus 3 equals 4". In contrast, PBT defines a universal property such as "for any two numbers you add, the result is the same regardless of the order of addition".

The left diagram represents EBT, and the right diagram represents PBT. While EBT requires manually creating and verifying test cases, PBT involves defining properties and testing them with random inputs.

In other words, EBT is strong against predictable bugs, whereas PBT has the potential to uncover unforeseen bugs. You will see this difference in the later UI rendering tests.

3. Why I Chose 'Ticket Management' as the Example

#As an explanation of Kiro + PBT, there is a Medium article[4] using a "room navigation game" as the example.

This game is very well suited to PBT due to the following structure:

State × Operation × Invariant (Property)

I thought the same structure appears frequently in business applications, so this time I chose "Ticket Management" as one such example.

Ticket management has the following characteristics:

- Constraints on state transitions

- Invariant conditions for terminal states

- Re-execution and order dependencies

- Assurance of error scenarios

These are properties that are hard to catch with example-based tests but pair well with PBT. Therefore, I chose ticket management as the example with practical application in mind.

4. Specification: Extremely Simple Ticket Management

#This time, I deliberately simplified the specification as much as possible.

Ticket Status

#Status = { Open, InProgress, Done }

- Only the three states above

Allowed State Transitions

#Open → InProgress

InProgress → Done

- All transitions other than the above are invalid

- Done is a terminal state and does not accept any operations

I will now input this minimal specification into Kiro.

5. Running Property-Based Testing with Kiro

#5-1. Generating the Requirements Document (requirements.md)

#First, enter the following requirements into the Kiro IDE:

- Create a GUI-based simple ticket management app

- No persistence required; make it a minimal app for verification

- Tickets must always have one of three states

- States can only transition in one direction: "Open→InProgress→Done"

- Cannot transition from the Done state to other states

- State updates are triggered by pressing a button

- Limit functionality to creation, listing, and state updates

- Want to verify state transition rules as invariants using PBT

A requirements document like the following was generated. The acceptance criteria are clearly verbalized in the EARS notation[5] ('Easy Approach to Requirements Syntax: rules for requirement definition syntax').

### Requirement 3

**User Story:** As a user, I want to update a ticket's status to accurately reflect the progress of the work.

#### Acceptance Criteria

1. WHEN the user presses the status update button on an Open ticket THEN Ticket_System SHALL change that ticket to InProgress

2. WHEN the user presses the status update button on an InProgress ticket THEN Ticket_System SHALL change that ticket to Done

3. WHEN a ticket is in the Done state THEN Ticket_System SHALL disable the status update button

4. WHEN a state transition is executed THEN Ticket_System SHALL allow only the sequence from Open to InProgress and from InProgress to Done

5. WHEN an attempt is made to change the status of a Done ticket THEN Ticket_System SHALL reject the operation and maintain the current state

What especially caught my attention was that descriptions such as invalid transitions being rejected, operations disabled in the Done state, and constraints on the order of state transitions—which would tie into subsequent property definitions—were made explicit.

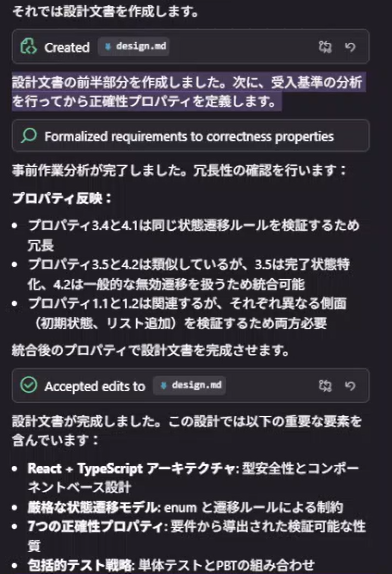

5-2. Design Document (design.md) and Property Definitions

#When generating the design document, Kiro declared the following:

I have created the first half of the design document. Next, I will analyze the acceptance criteria and then define correctness properties.

An excerpt of the output was as follows. Properties are explicitly output as design artifacts.

### Property 1: Initial State on Ticket Creation

*For any* valid title, when creating a new ticket, that ticket is always created in the Open state

### Property 2: List Addition on Ticket Creation

*For any* ticket list and valid title, when creating a new ticket, the list size increases by 1 and the new ticket is included in the list

### Property 3: Completeness of Ticket Display

*For any* ticket, the rendered result of that ticket includes the title and current status information

### Property 4: Execution of Valid State Transitions

*For any* ticket and valid transition (Open→InProgress, InProgress→Done), when performing a status update operation, the ticket's status changes to the expected next state

### Property 5: Rejection of Invalid State Transitions

*For any* ticket and invalid transition, even when performing a status update operation, the ticket's status does not change

### Property 6: Operation Disabled in Done State

*For any* ticket in the Done state, the status update button is disabled and the operation cannot be performed

### Property 7: Maintenance of System Invariants

*For any* operation (creation, status update), after execution, all tickets in the system are in a valid state (Open, InProgress, or Done)

As a result, not only state transitions, but also invariants on initial state, completeness of display contents, and system-wide invariants—in other words, seven properties in total, including properties that were not explicitly requested—were defined.

5-3. Implementation Plan (tasks.md) and Property Traceability

#The following implementation plan was output:

- [ ] 2. Business Logic Layer

- [ ] 2.1 Create tests for state transition logic

- **Property 4: Execution of Valid State Transitions** (Requirements 3.1, 3.2, 3.4)

- **Property 5: Rejection of Invalid State Transitions** (Requirements 3.5, 4.2)

- _Requirements: 3.1, 3.2, 3.4, 3.5, 4.2_

- [ ] 2.2 Implement state transition functions

- Logic to determine valid transitions

- Implementation of status update processing

- Run tests and verify passing

- _Requirements: 3.1, 3.2, 3.4, 3.5_

In tasks.md, properties, requirements, tests, and implementation tasks are mapped, making it possible to trace "why this test exists."

Also, since the test-first principle of TDD was adopted, the following flow naturally emerged:

Test creation → Implementation

For AI-driven development using TDD, please also refer to the following article.

5-4. Implementation and a Concrete Example of PBT

#The state transition properties were implemented as PBT using fast-check[6].

Here is a sample of the written test code. It verifies that the transition properties always hold for any title and any valid state.

test('Transition from PENDING to IN_PROGRESS is executed correctly', () => {

fc.assert(

fc.property(validTitleArb, (title) => {

const ticket: Ticket = {

title,

status: TicketStatus.PENDING

};

// The transition from PENDING to IN_PROGRESS is valid

const isValid = isValidTransition(ticket.status, TicketStatus.IN_PROGRESS);

const nextStatus = getNextStatus(ticket.status);

expect(isValid).toBe(true);

expect(nextStatus).toBe(TicketStatus.IN_PROGRESS);

}),

{ numRuns: 100 }

);

});

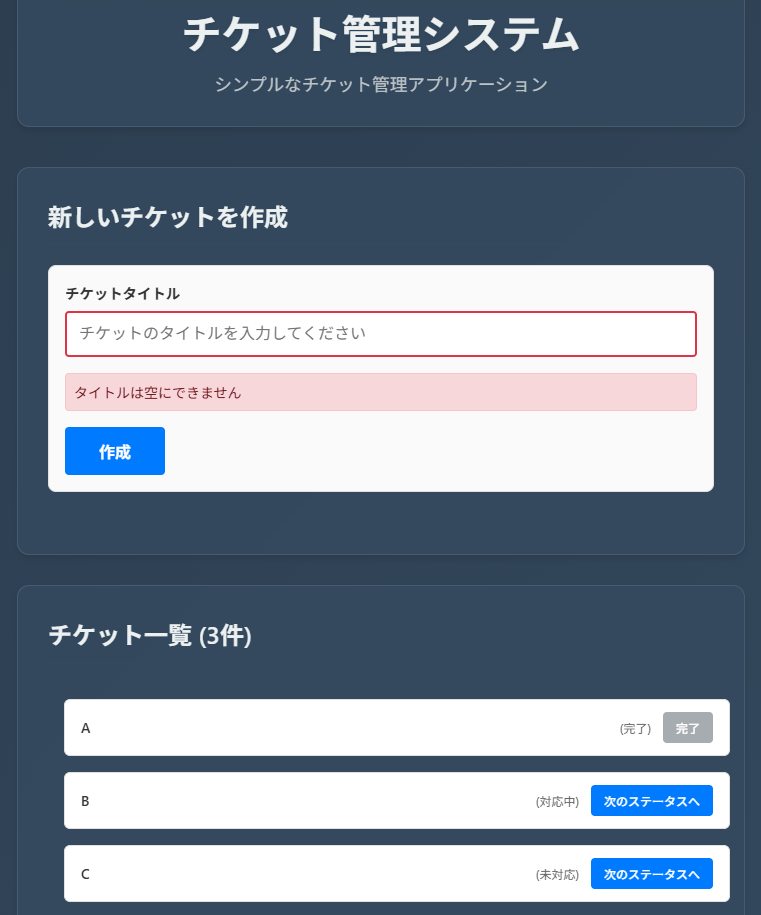

5-5. Operation Verification

#I checked the behavior by registering some tickets in the finished UI and inducing errors.

6. Conclusion: What I Learned by Implementing PBT in Kiro

#To be honest, I felt that the awesomeness of PBT is hard to grasp with only state transitions. Because the state transition rules this time are so simple that they can be adequately verified with example-based tests.

However, things change dramatically when it comes to properties related to UI presentation.

Unexpected Discoveries

#In the property tests for ticket title display, issues that I had not considered as part of the specification were detected, such as consecutive spaces being normalized by HTML, and ambiguous handling of leading/trailing spaces or titles consisting only of spaces.

I believe these would not have come up as test points in manual testing or example-based testing.

From this experience, I realized that the value of PBT lies not in "exhaustively trying all cases" but in "bringing to light inputs or assumptions that people had not anticipated."

7. Closing Remarks

#By using Kiro, I felt the following:

- The psychological and implementation barriers to introducing PBT have definitely been lowered.

- You can connect specifications, design, and tests around properties.

This time it was at the unit level, but using it in integration tests or system tests also seems valuable.

The repository used this time is published below. (It may be made private without notice)

Takuto Wada. Positioning of Property-based Testing / Intro to Property-based Testing. Speaker Deck. ↩︎

Amazon Web Services. Kiro: New Tool That Enhances IDE and Command Line Features with Generative AI Now Generally Available. AWS Blog, 2025. ↩︎

Fred Hebert, Leonid Rozenberg. 実践プロパティベーステスト ― PropErとErlang/Elixirではじめよう. ラムダノート, 2023. ↩︎

Matheus Evangelista. Building Smarter with Kiro: A Hands-On Look at Property-Based Testing. Medium, 2025. ↩︎

Alistair Mavin. EARS: The Easy Approach to Requirements Syntax. ↩︎

fast-check. fast-check. ↩︎